Contents

While writing your term paper or thesis, it is imperative that you include a record of all the sources you have used in your writing in a consistent format that is widely understood and accepted.

There are many accepted conventions for citing sources. Our subunit will follow the system outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style, which is widely used in English-speaking countries. Note: Understanding how one system works will equip you with the knowledge required to use other systems (called “style guides”). The system outlined by Matthew Gardner and Sara Springfeld in Musikwissenschaftliches Arbeiten: eine Einführung serves as a standard reference for musicological scholarship in Germany. For comparison, you may refer to the German version of this lesson.

You may use either system for your university assignments – choose one and keep consistent! However, always check with your lecturers or thesis supervisor if they have a preference as to which system you should use (or if they have their own preferred style sheet that is different from the two found in this online handbook).

Every piece of scholarly writing is based on factual information derived from reliable sources – both primary and secondary sources. All these sources must be disclosed in compliance with good scholarship practices. This must be done for two reasons (Herbert 2009, p. 71):

- to give due credit to the person or people who created the source that you are using

- to provide information for your readers that will enable them to trace your sources and see whether they share the conclusions you have drawn from them.

Failure to accurately identify citations or using other people’s work without proper acknowledgement results in plagiarism. This dishonest and unethical practice is a serious offence which will result in one failing the course for which the term paper was written or in the revocation of your degree should you be found guilty of plagiarism even at a later stage.

With the internet and various software, examiners can easily detect plagiarism and cases of using AI writing assistance.

The following subunits will take you through various aspects of scholarly documentation, which include:

- Citation – an introduction

- Plagiarism

- The notes-and-bibliography system

(1) Citation – an introduction

What must be cited?

As a rule of thumb, any information or idea that did not originate from you must be referenced.

How must information be cited?

The precise acknowledgement of a source depends on how you use the information in your writing.

- Quoting word-for-word

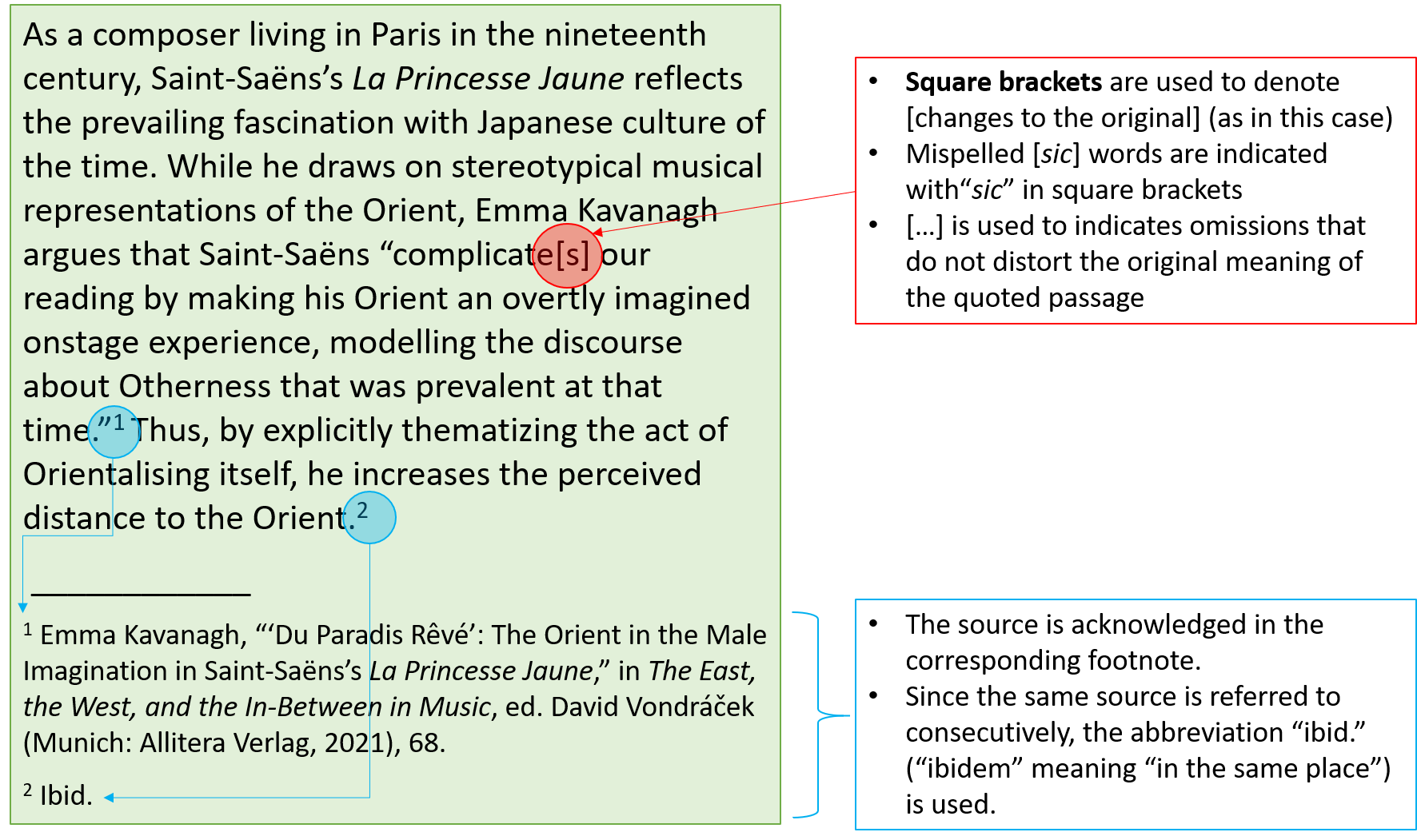

- “If you use a quote in its original wording you must place the copied sections verbatim (without modifications) in inverted commas, as shown in this bullet point.” The source of the quote is given in the corresponding footnote.

- Any changes to the original source must be “indicated [in square brackets] to clearly mark your modification.”

- Refer to Example 1, footnote 1 (see below).

- Paraphrasing

- If you use the ideas of other scholars but rephrase their writing (using your own words), you must still acknowledge your source in a footnote.

- Refer to Example 1, footnote 2 (see below).

- Directing attention to other sources

- A footnote may be used to direct readers to the works of other scholars even if you do not quote or paraphrase their work in your text.

- Refer to Example 2, point (e) (see below).

How much to cite?

While it is important to contextualize your ideas in relation to already existing scholarship, excessive citation is detrimental to the quality of your work: a flood of citations is not only distracting, but also detracts from your original analyses and ideas – which is your main contribution to the scholarly community. Bear in mind: a patchwork of citations is no replacement for independent scholarly inquiry!

A good balance must be found. Practice good judgement when referring to other works. Always ask yourself: how is this source relevant to my research question?

Take extra care and responsibility to avoid plagiarism as accidental plagiarism provides no absolution.

The exception: what does not need to be cited?

You do not need to cite facts that are considered common knowledge in your discipline. However, if you are not sure if this is considered so, it is always safer to cite it (and consult your supervisor/lecturer regarding this).

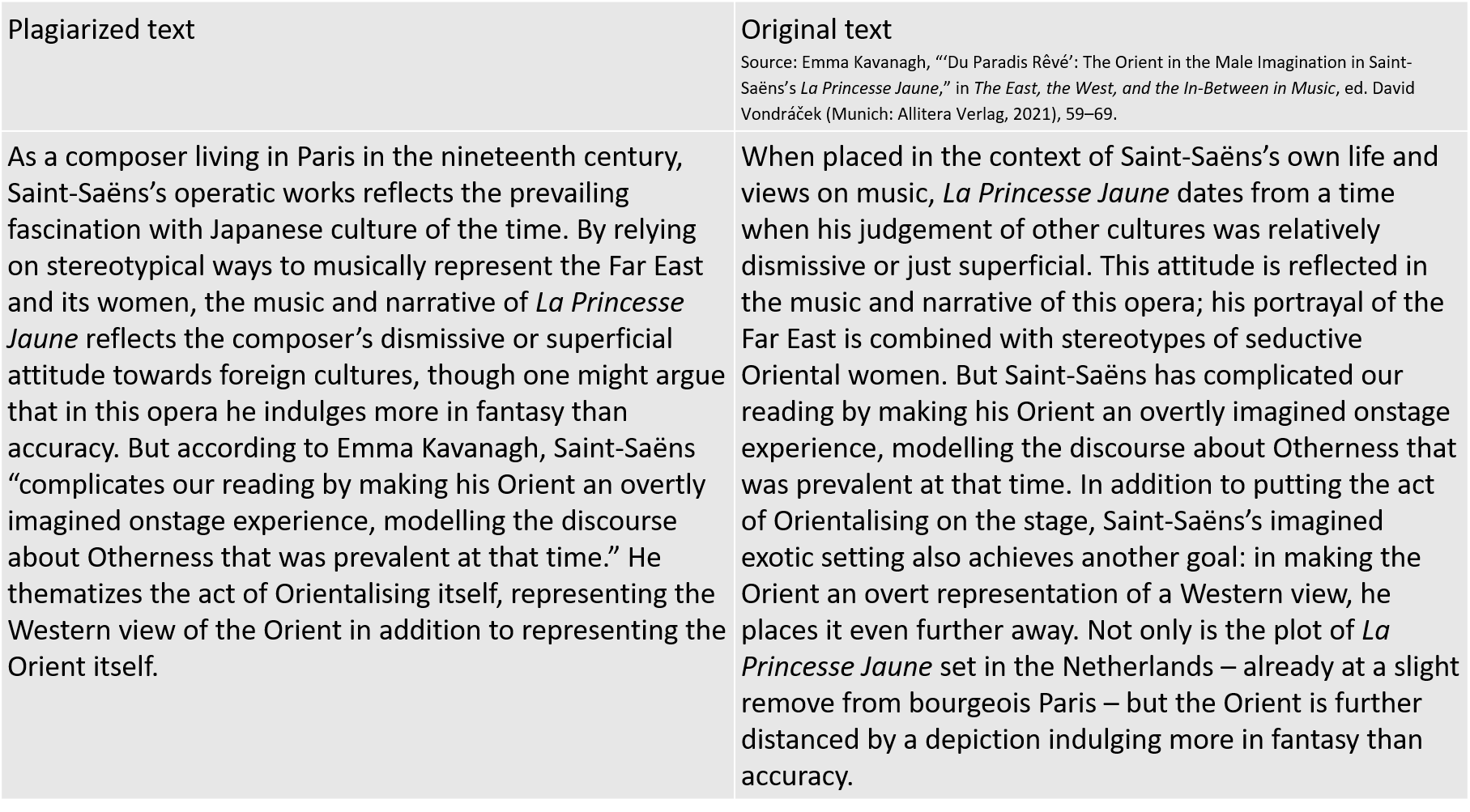

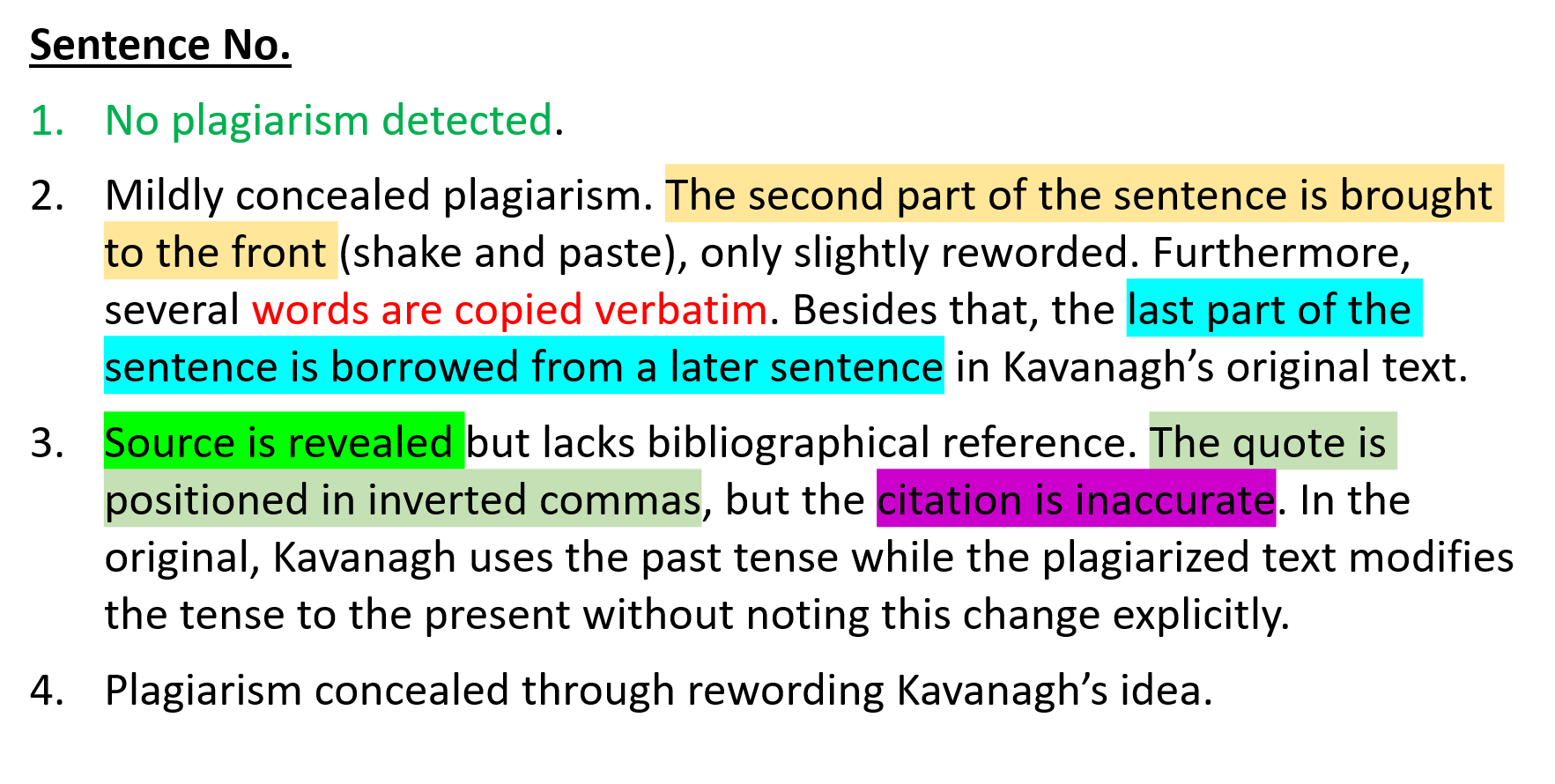

Common plagiarism cases:

1) Copy & paste

- Word-for-word copying (or merely changing a few words) without proper attribution (quotation marks + bibliographical reference)

2) Shake & paste

- Copying material and changing the order of sentences (or parts thereof) without proper attribution

3) Veiled plagiarism

- Rewording and restructuring of sentences without proper attribution

4) Translation plagiarism

- Translating works in a foreign language and claiming it as your own

Identify the plagiarism in the following text passage (left). The original text is found on the right.

Scroll right to reveal the solution

(3) The notes-and-bibliography system

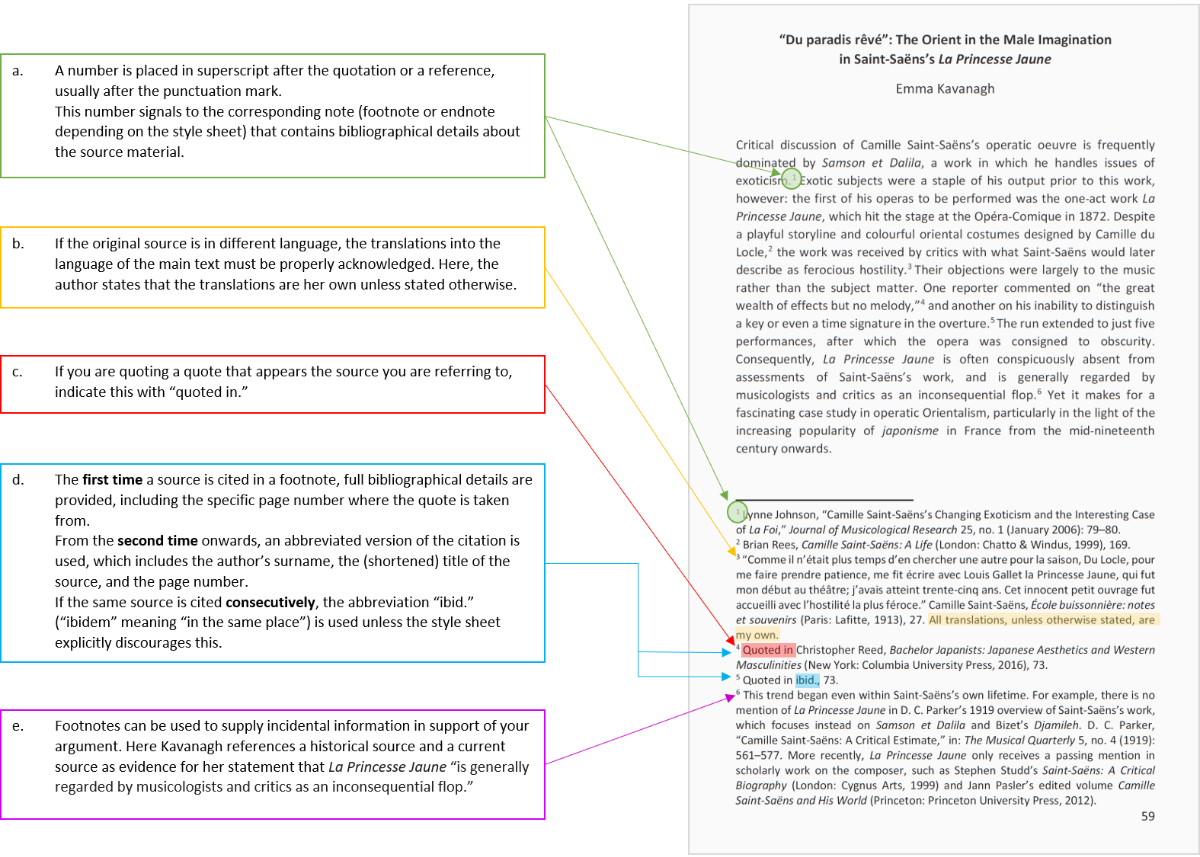

In the example shown below, the “notes and bibliography” system is used.

Example 2

Source: Emma Kavanagh, “‘Du Paradis Rêvé’: The Orient in the Male Imagination in Saint-Saëns’s La Princesse Jaune,” in The East, the West, and the In-Between in Music, ed. David Vondráček (Munich: Allitera Verlag, 2021), 59–69.

Footnotes

As the names suggest, footnotes appear at the bottom of the page.

Sometimes instead of footnotes, endnotes – which appear at the end of the main text body – are used. Both footnotes and endnotes carry the same content, but are found in different locations in scholarly publications. Word processing software generates footnotes or endnotes automatically. Refer to this OMA resource (in German) for more information.

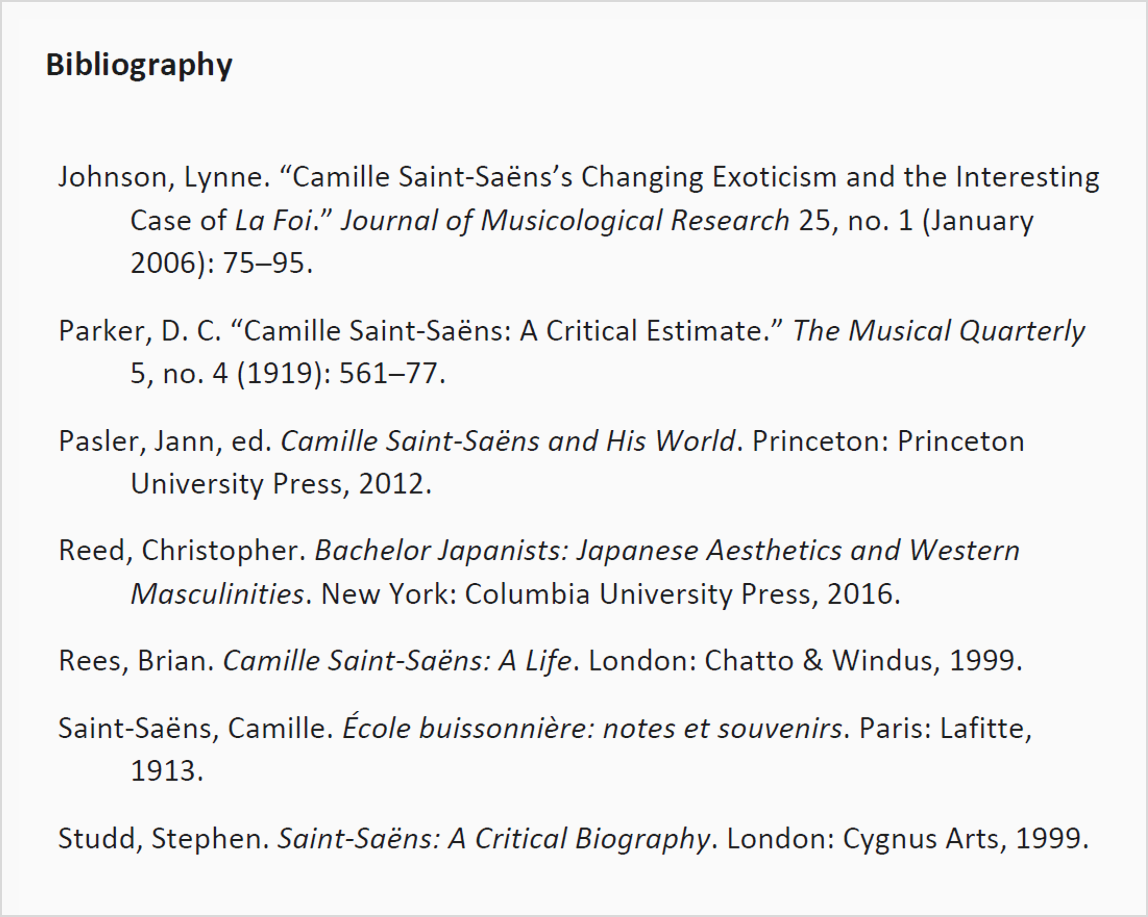

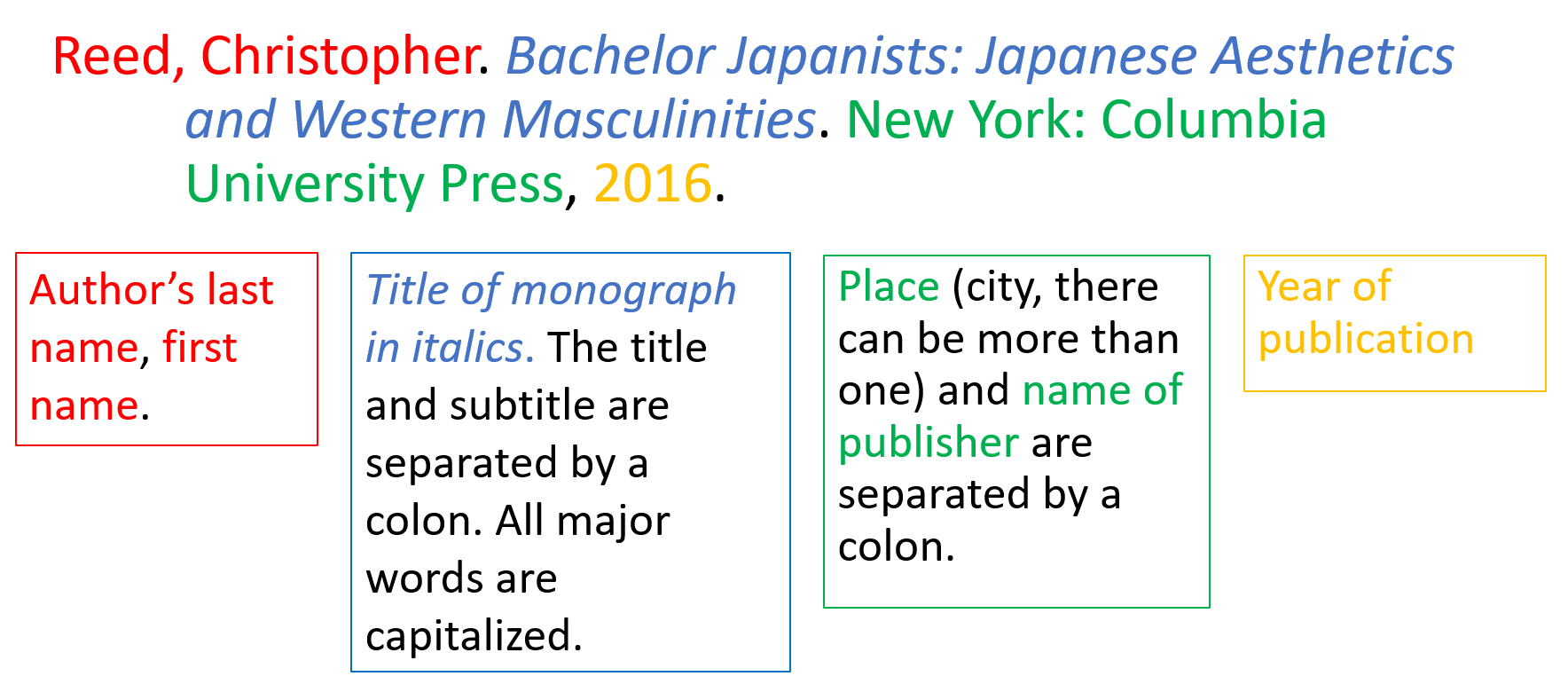

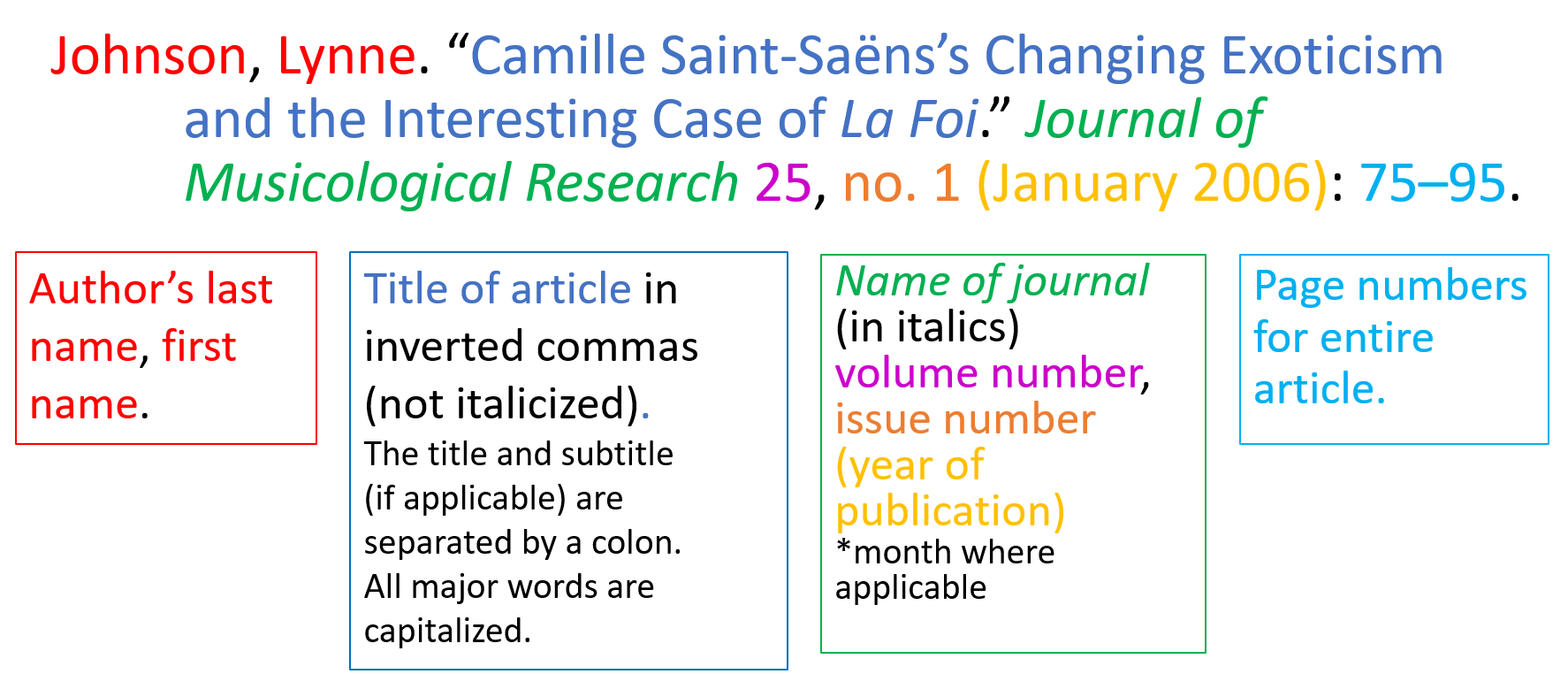

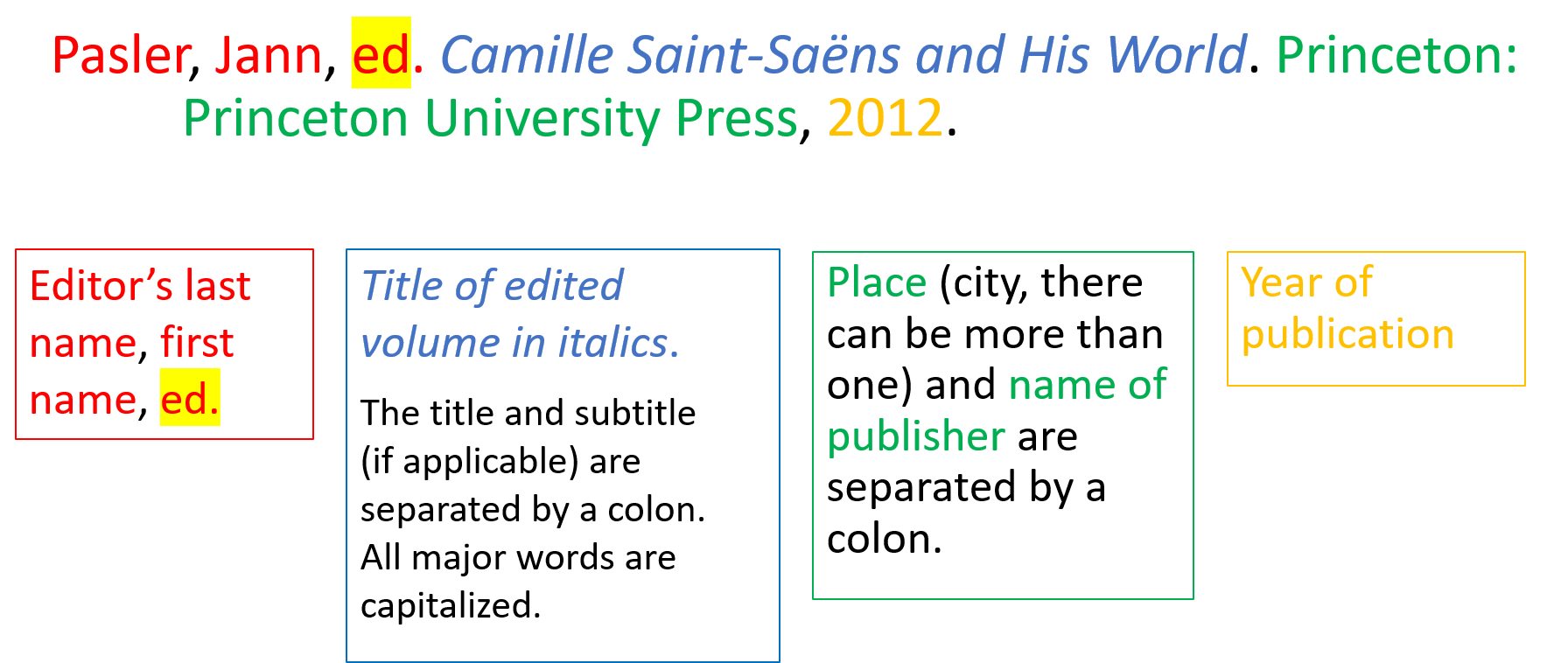

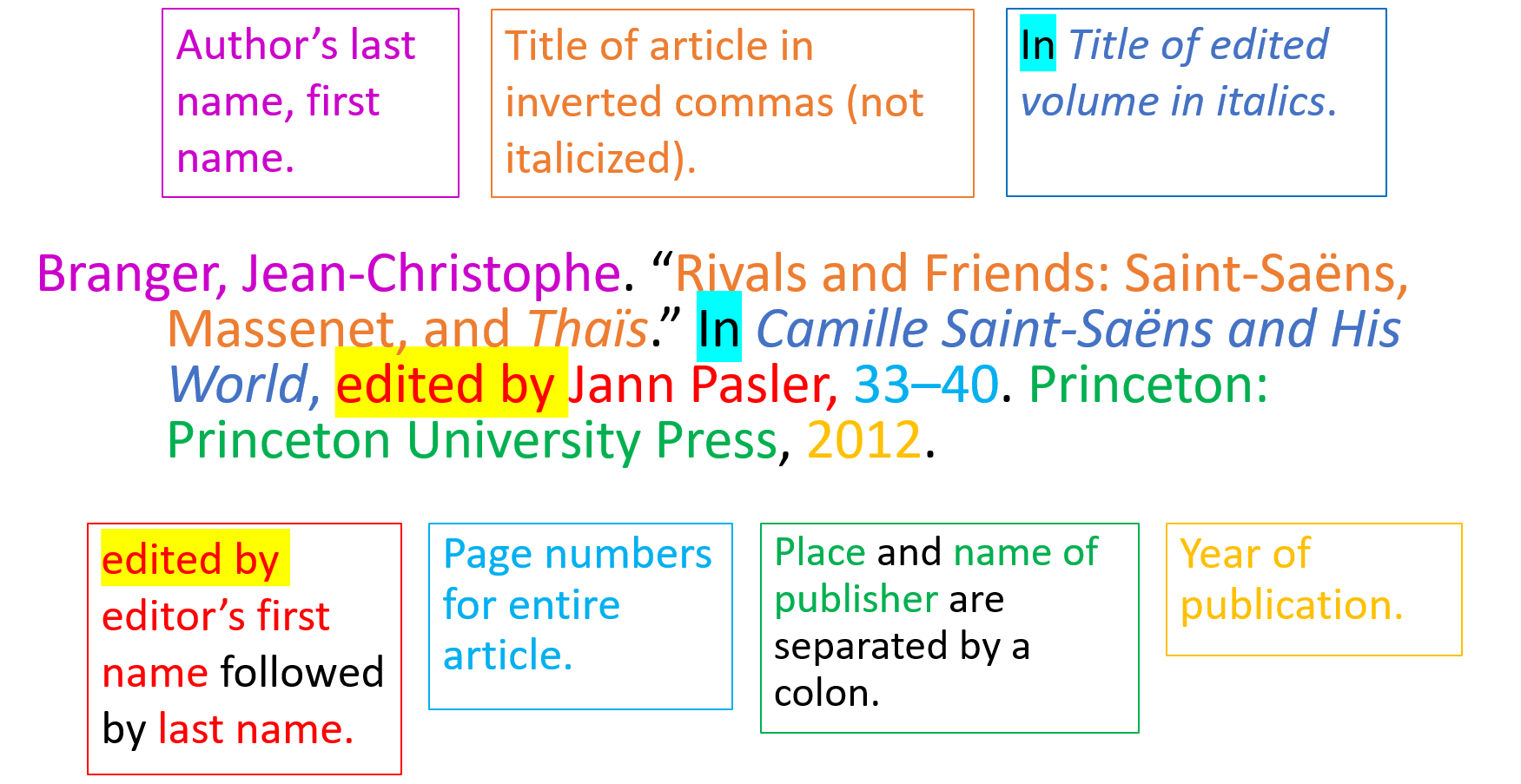

Bibliography

A bibliography is an alphabetical list of all reference materials used in a piece of scholarly writing. In longer published works such as monographs and theses, primary and secondary sources are listed separately. In shorter works such as journal articles and book chapters, primary and secondary sources are often listed together. Sometimes, journal articles forgo a bibliography altogether, meaning that the footnotes must contain all bibliographic information required for the reader to trace the source material.

In academic papers and theses, however, primary and secondary sources must always be listed separately.

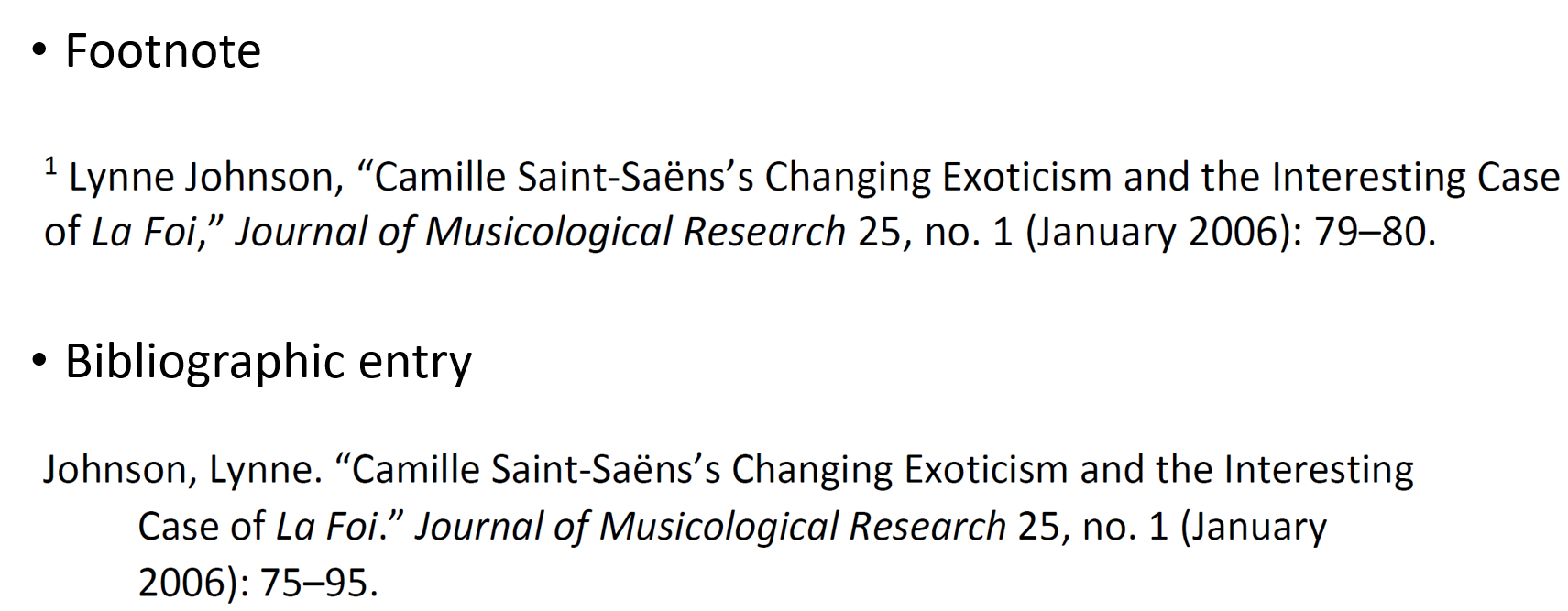

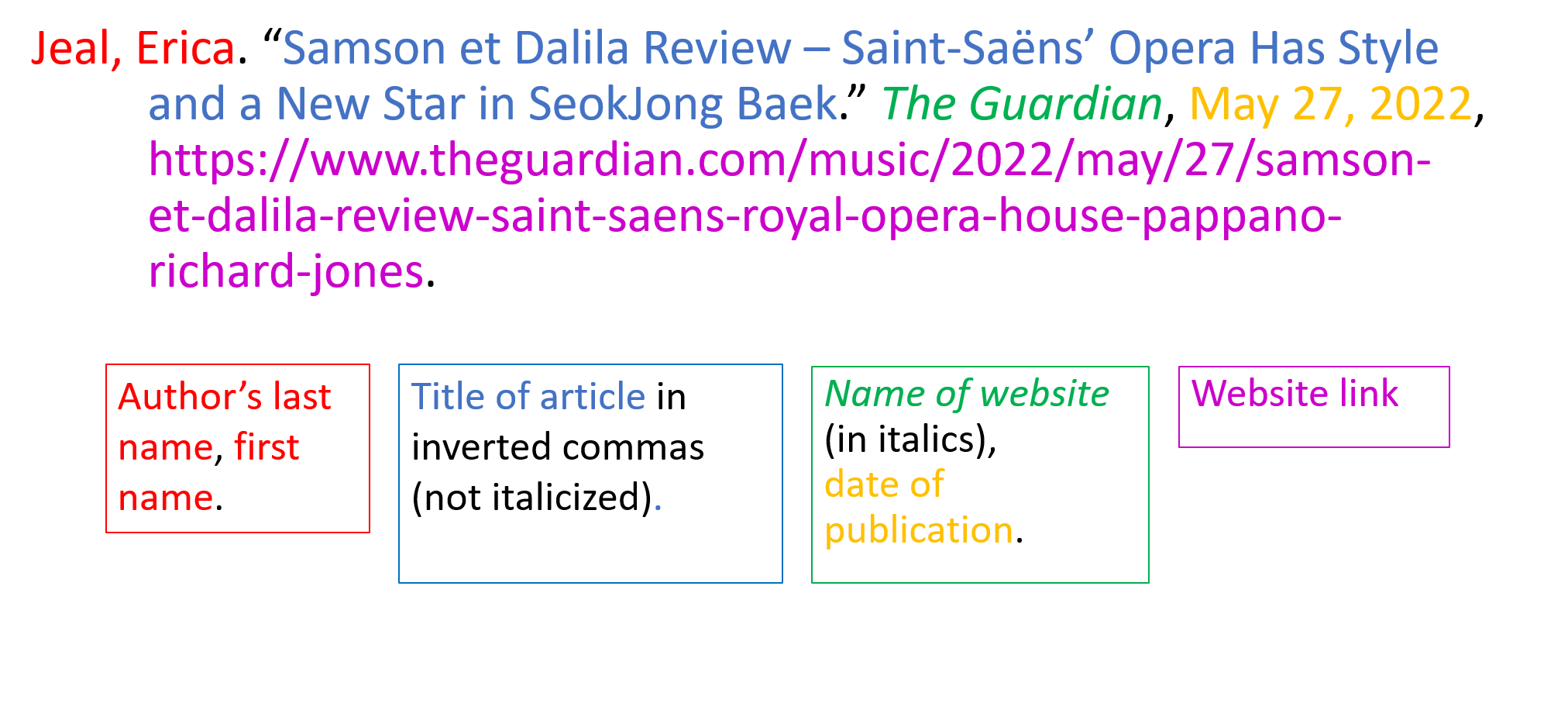

Taking for example the sources listed in Example 2, the bibliographical entries of these items will appear as follows:

Identify the differences between the entries that appear in the footnote (top ) and the bibliography (bottom) for the same source.

When you want to cite a chapter in an edited volume, include the reference to the specific chapter. References are often made to the edited volume as a whole when you want to give your readers an overview of the research that has been done in this area – here it is common to refer to the edited volume as a whole instead of listing each chapter out.

Although the Chicago Manual of Style requires only the date of publication for a website (where available), it is good practice to also include the date you accessed the website to clarify which version you are referring to (in case of future edits made to the website). This would enable scholars to verify the information you provided, for example, via the Wayback Machine.

Return to the bibliography above. Identify the types of source for each bibliographic entry (cfr. Lesson 4).

Reference

- Emma Kavanagh, “‘Du Paradis Rêvé’: The Orient in the Male Imagination in Saint-Saëns’s La Princesse Jaune,” in The East, the West, and the In-Between in Music, ed. David Vondráček (Munich: Allitera Verlag, 2021), 59–69.

Further reading

- Trevor Herbert, Music in Words: A Guide to Researching and Writing about Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 70–86, 174–197, also 198–219.

- Matthew Gardner and Sara Springfeld, Musikwissenschaftliches Arbeiten: eine Einführung, 2nd edition (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2018), 251–284.